Cultural exploitation of Mexican indigenous handcrafts art, a $35 billion industry

The plagiarism of indigenous handicrafts art, a $35 billion industry and Mexico’s new laws to protect this copy righted art won’t stop the piracy.

Mexican law specialists point out that the approved reform passed by the Mexican congress last year is insufficient to protect the ten thousand years-old cultural legacy of indigenous peoples.

In the current world of globalization and digital commerce, cultural identity of Mexico is now for sale, but it is not the people who keep the profits.

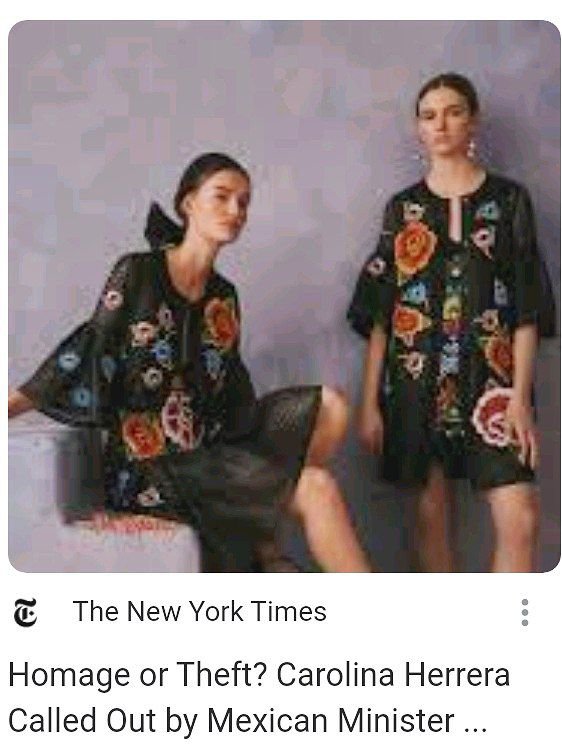

While a serape (shawl) handcrafted by Saltillo artisans can cost between 500 and 3,000 Mexican pesos (approximately $25 to $150), a brand like Carolina Herrera or Louis Vuitton, whom have plagiarized the indigenous art patterns, can sell an identical piece for $1,000 and $4,000 (dollars).

Carolina Herrera’s collection uses colorful embroidery of animals and flowers which the Mexican government points out, is one of many dresses in Herrera’s collection that “this embroidery comes from the community of Tenango de Doria (Hidalgo); in these embroideries is the very history of the community and each element has a personal, family and community meaning”.

The visual appeal of the embroideries textiles, sculptures, paintings and other handicrafts that tells an ancestral story of Mexico, have compelled hundreds of companies, and dozens of large brands to appropriate and profit from the cultural heritage of the original peoples of Mexico, without their creators seeing a single penny for their art work, effort and creativity.

Last year, in April, Mexico’s congress approved, by an overwhelming majority, a reform amendment to the Federal Copyright Law, to recognize the works of indigenous peoples and communities as “object of copyright protection and intellectual property”. The law protects the collective work of the indigenous people for the first time.

But the law still has to reflect an economic improvement to the indigenous artist who now legally own the art but still aren’t getting compensated for their art.

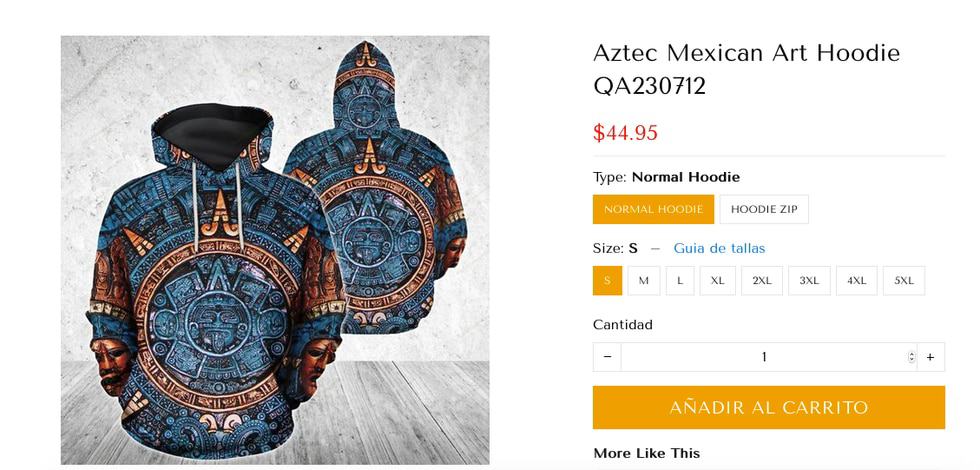

Dozens of companies, many from Asian origins, use the internet to sell Mexican artwork to profit from the aesthetics of indigenous peoples without any Mexican law being able to do anything about it.

Carlos Martinez Negrete, cultural promoter and human rights defender of indigenous peoples, indicates in an interview that the reform approved by the legislators is insufficient. “The impact on communities is generated in digital advertising and in the empathy that a brand generates with the consumer, through a false social responsibility,” he says.

Sculptures, paintings, but mainly textiles that imitate the aesthetics of native peoples of Latin America and Mexico, are sold through the internet from five to 50 dollars.

The embroideries of Tenango de Doria (Hidalgo), huipiles that imitate the elaborations of Oaxaca or t-shirts stamped with the Stone of the Sun (the Aztec calendar), are sold on Amazon and other internet pages that constantly change their address, name, and place of origin, so they are hard to track.

Online outlets run amok profiting from Mexican ancestral art work.

But piracy is not enough for these eluding online sellers, indigenous art crafts are sold on Amazon with a racist and classist titles. For example, this other user is selling a dress with indigenous art using the title: Mexican peasant.

A user review commented, “That is not a Mexican Peasant dress. It’s an indigenous artisanal dress which are made in Mexico and many parts of LATAM. Unless you people think an indigenous person is a peasant. This is unreal!!”

Intangible heritage of more than ten thousand years of Mexicos Mayan and Aztec ancestry.

Other most visible cases of cultural expropriation have occurred by recognized brands such as Zara (owned by Inditex), Nestlé or Mango, all of them between 2014 and 2019. Mexico tried to fight back, the National Human Rights Commission issued a recommendation in which it ‘warned’ that “Mexico does not have an adequate legal framework that addresses the specificities and characteristics of indigenous peoples and communities, even one that makes effective their right to protection” of their cultural heritage.

For Martínez Negrete, the protection of the artistic creations of native peoples not only has to come from a law, but from local governments. “All the deputies, out of supposed empathy, claim to protect the cultural elements of indigenous peoples, but in fact they continue to be commercially abused,” he comments.

Despite their rich cultural and artistic heritage, Mexico’s indigenous communities live in extreme poverty. 72% of people belonging to an indigenous population are victims of this situation, according to figures from the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (Coneval).

Additionally, most artisans in Mexico lose between 25 and 30% of their profits due to brands expropriating their art work and selling them at large retail stores at a cheaper price, according to a survey conducted by the Network of Artisans and Producers of Mexico City.

Sources: El Universal